Medellín

Medellín, the capital city of the Antioquia province in northwestern Colombia, was the undisputed ‘murder capital’ of the world in the early 1990s. In the waning days of Pablo Escobar’s infamous Medellín cartel and the years immediately following Escobar’s death in December 1993, homicide rates reached record levels, peaking in 1991 at 381 per 100,000 inhabitants.

Only after 2002 homicide rates would fall to more average Latin American levels. Since then, much has been made of Medellín as a spectacular success story. It is often labeled the Medellín ‘renaissance’ or Medellín’s internationally applauded model of ‘social urbanism’.

At the neighborhood level steps were taken to expel or neutralize the various armed groups, to invest in community services, and to install a system of participatory budgeting. At the city level, eye catching interventions, often with the support of the powerful business community, was the extension of cable cars to the already existing metro system to connect the uphill poorer communities to the downtown, industrial, and affluent neighborhoods on the valley floor.

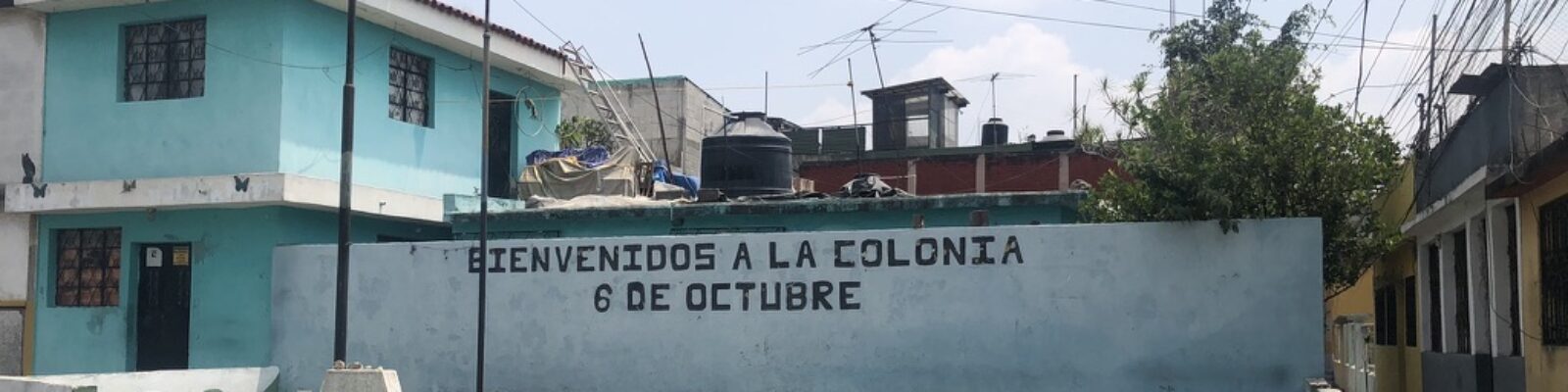

Other socio-spatial interventions were urban upgrading projects, other infrastructure such as public escalators, community libraries, green areas, etc. The period of social urbanism facilitated the emergence of a wide range of community level social, political and cultural groups and initiatives in Medellín’s urban margins (generally called comunas), most notably in Comuna 13 San Javier.

Yet, although Medellín seems to be putting a strategy of transformative multi-level resilience into effective practice, there are of course flip sides. The most often cited downsides are, first, the continued presence of non-state armed groups in the comunas, in particular local gangs and a new generation of paramilitary/drug trafficking groups, arguably in some ways in tacit pacts with the legal state. Second, the weight of elite priorities in Medellín’s urbanism is criticized for producing gentrification and serving city branding for investors and tourists.